Nearly three in four of us will face extreme weather changes within the next two decades, a new study predicts.

“At best, we calculate that the rapid changes will affect 1.5 billion people,” says physicist Bjørn Samset of the Center for International Climate Research (CICERO) in Norway.

This lower rating will only be achieved by dramatically reducing greenhouse gas emissions – something that has not yet happened.

Otherwise, CICERO climate scientist Carley Iles and his colleagues’ modeling finds that if we continue on our current course, these dangerous changes will hit 70 percent of Earth’s human population.

Their modeling also suggests that many of those to come are already locked in.

“The only way to deal with this is to prepare for a situation with a much higher probability of unprecedented extreme events already in the next one to two decades,” explains Samset.

We have already lived examples of these extremes.

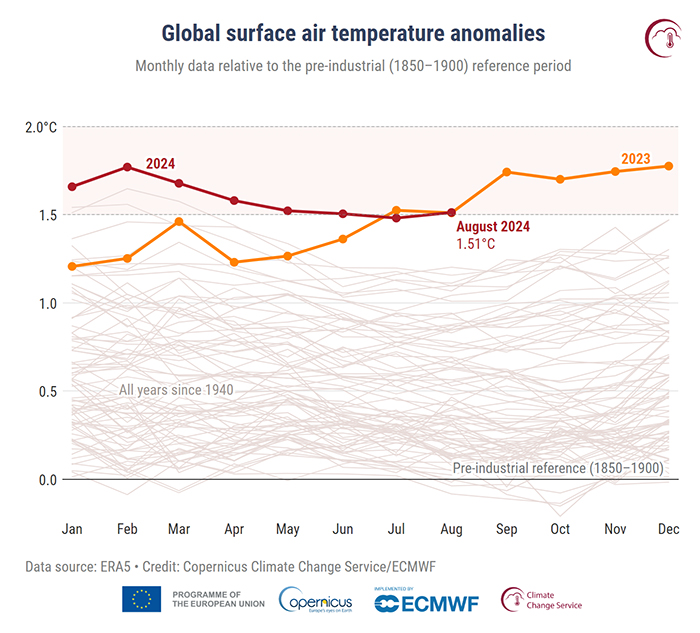

Data from Europe’s Copernicus climate service shows that Earth just had its hottest Northern Hemisphere summer on record. The previous record was just last year. The southern hemisphere has also experienced a record warm winter.

This increase in global temperature has brought with it fatal fires, floods, storms and droughts that are destroying crops and leading to more and more widespread hunger, creating favorable conditions for the spread of more diseases.

“Like people living in a war zone with the constant banging of bombs and the clanking of guns, we are becoming deaf to what should be alarm bells and air raid sirens,” Research Center scientist Seth Borenstein told the Associated Press. Climate Woodwell, Jennifer Francis. Press, in response to new Copernicus data.

Modeling by Iles and team suggests further extreme weather changes will occur even faster than we’ve seen so far. This increases the chances that more dangerous extremes in temperature, rain and winds can occur in succession or even simultaneously.

For example, increased dry lightning combined with greater drought conditions is creating more frequent and intense wildfires around the world. And in 2022, a severe heat wave in Pakistan was immediately followed by unprecedented floods, affecting millions of people.

“Society appears particularly vulnerable to high rates of change in extremes, especially when multiple risks are simultaneously increased,” the team explains in their paper.

“Heat waves can cause heat stress and excess mortality of both humans and livestock, stress on ecosystems, reduced agricultural yields, difficulties in cooling power plants and transport disruptions.

“Similarly, rainfall extremes can lead to flooding and damage to settlements, infrastructure, crops and ecosystems, increased erosion and reduced water quality.”

On our current trajectory of high emissions, the tropics and subtropics in particular, where most people call home, will face the greatest weather extremes.

“We focus on regional changes, due to their increasing importance to the experience of people and ecosystems compared to the global average, and identify regions that are projected to experience substantial changes in the rates of one or more extreme event indices over decades of future,” says Iles. .

With drastic cuts in emissions we can reduce some of these impacts, but this will also cause more immediate problems in some regions.

“While cleaning the air is critical for health reasons, air pollution has also masked some of the effects of global warming,” explains meteorologist Laura Wilcox from the University of Reading in England.

“Now, the necessary cleanup could combine with global warming to produce very strong changes in extreme conditions over the coming decades. The rapid cleanup of air pollution, mainly over Asia, leads to accelerated increases in warm extremes and influences the summer monsoons in Asia”.

But inaction means these extremes of worsening weather are likely to affect most of us in the very near future.

You can see the types of climate change expected in your home area on an interactive map here.

“These conclusions highlight the need for continued mitigation and adaptation to potentially unprecedented changes over the next 20 years even in a low-emissions scenario,” Iles and colleagues write.

This research was published in Nature Geoscience.